International Translation Day 2021 - Celebrating 300 Languages on StoryWeaver!

Posted by Asawari Ghatage on February 17, 2022September 30 is International Translation Day - a day that is very important to us at StoryWeaver.

For children to become readers, they must have access to books in the languages they speak and understand. Yet, this is sorely lacking in several parts of the world — there are not enough books, in not enough languages for children to learn and practise reading. A UNESCO study states that 40% of the world does not have access to education in their mother tongue.

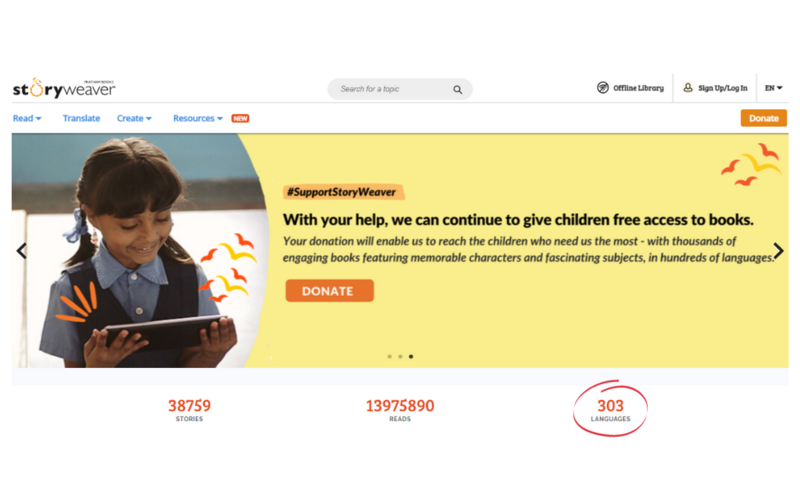

In September 2015, Pratham Books set up StoryWeaver with the aim of addressing this scarcity of books for children. StoryWeaver was launched with 800 books in 24 languages. Today, just 6 years later, the platform offers over 38,000 books, and our language footprint has grown to 303 languages - 60% of these languages are indigenous.

In the coming days, we shall share more insights about the guiding principles that have helped us nurture an ecosystem to address the dearth of children’s books in mother tongue languages.

We want to say a big thank you to our wonderful translation community, our partners and collaborators that have helped us grow and learn on this journey to the 300 languages milestone on StoryWeaver. Here’s to more storybooks in more languages, so that more children around the world can experience the joy of reading!

comments (2)#FreedomtoRead 2019: Ankit Dwivedi on how stories in Bundelkhandi can impact children in his home state

Posted by Asawari Ghatage on February 19, 2019Ph.D. scholar and researcher Ankit Dwivedi loves to write and tell stories. He is translating stories into Bundeli or Bundelkhandi language. He is a native of Lalitpur, a city that lies at the heart of Bundelkhand. He speaks the dialect of Bundelkhandi and uses the Devanagri script to write it. Ankit’s research work during his Masters's programme has been a qualitative study of a local language newspaper run by women which have influenced him to explore local language learning possibilities for children. Though there are millions, according to Ankit, who speaks Bundelkhandi language, there is a dearth of interesting and engaging reading material for children in the region. Ankit wants to change all of that by translating and creating a digital library of books in Bundelkhandi. In an email interview he tells us the challenges of translating in his mother tongue and how stories can make for the best company in the world.

Where is Bundelkhandi Spoken?

The Bundelkhandi language is an Indo-Aryan tongue that is spoken in central India's Bundelkhand area. It is a member of the Western Hindi cluster of Central Indo-Ayran languages. Devanagri script is used to write the Bundeli language words.

The poems of the Alha-Khand epic are early instances of Bundelkhandi literature. In the Banaphari area, bards continue to preserve it. The epic tells the story of heroes from the 12th century CE. The age of Emperor Akbar is when formal Bundeli literature was first produced. Kesab Das, a poet from the sixteenth century, is one notable author. During the nineteenth century, Padmakar Bhatt and Prajnes both produced a number of works. At the Chhatrasal of Panna's court, Prannath and Lal Kabi produced a large number of works in the Bundeli language.

Bundelkhandi Language And Its Origins

Rajputs and various other warlike tribes used to primarily speak the Bundelkhandi language. Additionally, it is regarded as an Indo-Aryan language and is mostly spoken in Madhya Pradesh's Bundelkhand area. It is also spoken in various areas of Uttar Pradesh, usually more so in the south.

Bundeli is, however, mostly regarded as the western form of Hindi. It is traditionally connected to Braj Language and was only largely spoken in the north Indian region till the 19th century. There are allegedly 20 distinct ways to speak in this verbal communication.

There are up to 20 million native speakers of this vocal communication. It employs the Devanagari script as its writing system. Even in Madhya Pradesh, the biggest state in India with an area of around 443446 square kilometers, it is recognised as the most often used expression.

This Is What A Bundelkhandi Language Translator Has To Say

Ankit wants to change all of that by translating and creating a digital library of books in Bundelkhandi. In an email interview, he tells us the challenges of translating in his mother tongue and how stories can make for the best company in the world.

Why did you decide to translate storybooks to Bundelkhandi as part of Freedom to Read?

It is always a pleasure to read in the language we have grown up speaking. I realised that there weren't too many many stories or picture books in Bundelkhandi. So, this is my effort and a little step towards building a digital library in Bundelkhandi that is free and accessible to all.

Describe your process of translations and how long does it take usually?

I translate those stories that I enjoy myself as a reader. I spend some time capturing the essence of the story in the original language and wondering how it may be preserved in the language I am translating to. Then, comes the play with words. Reading it out loud helps. As for time, I would say, sometimes it takes two to three hours to translate a story. And sometimes, edits may take days.

What kind of a person do you think makes the best kind of translator for children’s stories?

I believe children use their senses in a much more mindful way than adults. They don’t just want to walk through a garden, they want to taste it, smell it and they want to know how everybody who is living and breathing there feels. For adults, seeing the world from the child's perspective can be an effort and practice. Those who are willing to make that effort can be great at writing, illustrating or translating children’s stories.

What is the hardest thing about translating from English into Bundelkhandi? How do you navigate words or phrases that are tricky to translate?

It is definitely tricky. In Bundelkhandi, just like many other dialects, who is speaking and how one speaks shapes what is being said. Just to give an example, the "Kaay" sound in Bundelkhandi is used to call people out like ‘Hey there’, and make exclamatory remarks like ‘What! Really?’ or in an interrogative speech to ask ‘Why?’. So, while writing, one has to consider what possible meanings the reader might be making out of these. I offer translations to people who speak the language and see how they are reading it. Repeating this process many times over gets us a better draft.

Can you tell us anything about yourself and your job that would surprise us?

I work with stories as a researcher and a storyteller. They make for a great company and people of all ages need the warmth and love they bring. I have seen adults heartily enjoying the simple linear ‘we know what’s going to come’ stories and I have seen children engaging deeply as we peel the layers of complex grey characters. I hope as adults, we take children more seriously. And ourselves, maybe a little lesser.

How Does Learning a Native Language Help Children?

In a way that few other things can, learning a native language may make you feel more connected to your ancestors and culture. The ability to think in one's mother tongue might act as a constant reminder that one is culturally varied and can always retreat to one's "home."

In addition to facilitating communication and interpersonal connections, our native tongue also helps us to comprehend and appreciate our own and our predecessors' cultural heritage. For kids, especially those from various familial situations, it fosters an awareness and understanding that is beyond useful.

Not only that but young children who had access to age-appropriate books and literature in their mother tongue had better pre-literacy abilities than kids who only had access to books in their second language.

Furthermore, Children who initially learn to read in their mother tongue will find it simpler than children who never learn to read in their first language to learn to read in their second language.

Even though they must acquire new letters, sounds, and words to become proficient readers in a second language, children who can read in their mother tongue comprehend the process of reading.

You can read Bundelkhandi stories translated by Ankit here.

Be the first to comment.Celebrating International Mother Language Day in over 60 languages!

Posted by Asawari Ghatage on February 24, 2020Every year, StoryWeaver marks International Mother Language Day (IMLD) to remind us all that learning to read in one’s mother tongue early in school makes education more engaging, meaningful and enjoyable for children.

Suzanne Singh, Chairperson, Pratham Books, says: “Children love stories and they are an important part of a child’s growth and development. Children need storybooks that they can relate to and that are in languages that they speak and understand. Through StoryWeaver, we are trying to address the inequity in the availability of reading resources by providing open and free access to over 18,000 storybooks in 224 languages and fostering the respect for cultural and linguistic diversity.”

International Mother Language Day 2022

In 2020, we're ringing in International Mother Language Day by helping volunteers conduct more than 1000 reading sessions for children in over 60 languages! This week, volunteers from around the world are using StoryWeaver’s digital repository of multilingual storybooks to read to children in several languages, including mainstream Indian languages (Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu), indigenous languages (Kuvi, Pawari, Santali), vulnerable languages (Gondi, Korku), classical languages (Sanskrit) and other languages from around the world (Arabic, Igbo, Nepali).

30,000 schools in the state of Chhattisgarh, India (of which 15,000 are in tribal areas) have been encouraged to celebrate International Mother Language Day with StoryWeaver by giving children access to books and storytelling in indigenous languages like Gondi, Kurukh, Sadri and many more. Says Dr. M. Sudhish, Samagra Shiksha Chhattisgarh: “On January 26, the Honorable Chief Minister of Chattisgarh announced the use of mother tongue languages while teaching in classrooms. When we heard about StoryWeaver’s IMLD initiative, we felt that this was a great opportunity to take the Chief Minister’s mandate forward and bring mother tongue storytelling into the classroom.”

Additionally, we're also thrilled to announce the launch of open digital libraries in 16 underserved languages, marking the culmination of our Freedom to Read 2020 campaign, which aimed to create digital books in languages that have limited or no children’s books. Through our campaign, over 500 storybooks have been translated into languages such as Amharic (Ethiopia), Basa Jawa (Indonesia), Bodo, Tangkhul (vulnerable languages from North-East India), Kolami (vulnerable indigenous language from Maharashtra), Kochila Tharu and Rana Tharu (spoken in Nepal), Sindhi, and bilingual books in English-Surjapuri, to name a few.

International Mother Language Day 2022 | Theme

"Using technology for multilingual learning: Challenges and opportunities" is the focus of the 2022 International Mother Language Day, which highlights the potential of technology to enhance multilingual education and encourage the development of high-quality teaching and learning for all.

Some of the biggest problems in education today may be solved by technology. If it is governed by the fundamental concepts of inclusion and equality, efforts to ensure fair and inclusive lifetime opportunities to learn for everyone can be expedited. A crucial part of inclusion in education is mother tongue-based multilingual education.

Many nations used technology-based solutions during the COVID-19 school shut down to ensure that learning continued. However, a lot of students lacked the tools, internet access, resources, content, and human support they would have needed to pursue remote learning. Furthermore, the diversity of languages is not always reflected in the tools, programmes, and content of distant learning and teaching.

International Mother Language Day At StoryWeaver

These libraries have been co-created in collaboration with our partner organisations:

- Aripana Foundation

- Azad India Foundation

- Karunodaya Foundation

- Pragyam Foundation

- Ras Abebe Aregay Library

- Nepal Rana Tharu Samaj

- Institute for Multilingual Education (IMLi)

And our Language Champions:

- Amina Bouiali

- Bharti Menghani

- Dron Sahu

- Kaleab Getachew

- Marzieh Nezakat

- Minket Lepcha

- Nazanin Karimimakhsous

- Sanjib Chaudhary

- Themreichon Leisan

- Theresia Alit

A huge shout-out to our Freedom to Read partner organisations, Language Champions, and IMLD reading volunteers! Your efforts will go a long way in helping put a book in every child's hand. THANK YOU!

Stay tuned for more stories from the IMLD reading sessions and our Freedom to Read partners!

In the meanwhile, here are some happy moments from our ongoing International Mother Language Day celebrations:

From a reading session in English-Surjapuri conducted by Azad India Foundation in Kishanganj, Bihar

From a reading session in Arabic conducted at the Qatar National Library

From a reading session in Kolami, conducted at DIET Yavatmal to mark the launch of an open digital library of 100 Kolami storybooks, created by Institute for Multilingual Education (IMLi) and StoryWeaver

From a reading session in Maithili conducted by Aripana Foundation at Gyan Niketan Public School, Darbhanga, Bihar

From a reading session in Amharic, by Ras Abebe Aregay Library in Ethiopia

From a reading session in Karbi, conducted by Pragyam Foundation at Parijat Academy, Guwahati, Assam

From a reading session in Marwari conducted by SNS Foundation, Rajasthan

From a Nepali reading session conducted by Nepali Rana Tharu Samaj

From a reading session conducted in Mayurbhanj, Odisha

Do join the conversation by leaving your thoughts in the comments section below. You can also reach out to us through our social media channels: Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

comments (3)