StoryWeaver and Nature Conservation Foundation celebrate World Wildlife Day with the launch of books on India's wildlife

Posted by Pallavi Kamath on March 03, 2021Post written in collaboration with the team at Nature Conservation Foundation

On World Wildlife Day 2021, StoryWeaver is pleased to announce a partnership with the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), an organisation that works towards conservation of India’s unique wildlife heritage. The aim of this partnership is to create more stories about nature, birds, and wildlife, that inspire children to develop a love of the natural world that they will inherit.

Through these stories, NCF's scientists and naturalists who work in a range of wildlife habitats - from coral reefs and tropical rainforests to the high mountains of the Himalayas - relive their experience of studying and encountering the wild.

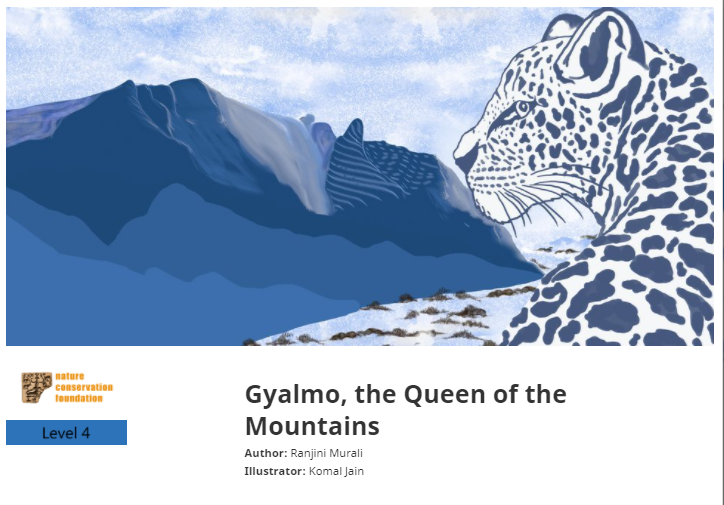

We are delighted to launch the first 2 books: Gyalmo, the Queen of the Mountains and Birds That Sing Their Name.

In Gyalmo, the Queen of the Mountains, Koyna and her friend Lobzang are in Spiti Valley, trying to spot the most elusive cat in the world, while Gyalmo, the snow leopard, watches from a distance as they try their best to see her. Read this humorous tale of humans and leopards by Ranjini Murali. Illustrated by Komal Jain.

In Birds That Sing Their Name, Jegan, a scientist working in bird conservation, talks about birds and the beautiful songs they sing in the wild. How do birds get their names? Sometimes people name them after their colours, size and food they eat. Sometimes, they get their names from the way they call or sing. Come meet some of the birds that sing their names. Read this riveting story on sounds by P Jeganathan, illustrated in watercolours by Ravi Jambhekar. We can still hear the echo of these songs!

Happy reading!

These books are an effort by the Nature Communications team at Nature Conservation Foundation to encourage awareness and appreciation of India’s wildlife in children and adults. We are delighted to have them on board as publishers on StoryWeaver.

Dive into the deep blue with these stories

Posted by Remya Padmadas on June 11, 2018The National Geographic's June issue is being widely shared on Social Media, thanks to its attention grabbing cover.

One of the most comprehensive studies on plastic polluttion estimates that 8 million tonnes of plastic went into the ocean in 2010. Oceans that are home to a stunning array of plant and animal life. These books remind us exactly who we share our planet with, and will hopefully help readers young and old think twice before reaching for a one time use plastic, that will mostly likely end up in someone elses home.

Dive! written and illustrated by Rajiv Eipe

Take a dive into the spectacular world of coral reefs, and catch a glimpse of some strange and beautiful sea creatures! Available in 14 languages, free to read, download and share.

Goby's Noisy Best Friend by Sheila Dhir and Anjora Noronha

We could all use a little help from our friends... even when you live in the ocean! Legless Goby and noisy Snap are best friends who live together in a burrow deep under the ocean. What happens when Goby gets tired of Snap’s loud claws?

Miss Bandicota Bengalensis Digs Up the Seashore by Aditi Ghosh and Sunaina Coelho

Miss Bandicota Bengalensis is an avid explorer. Every time she digs in a new direction she lands up in new and wondrous places! This time our unlikely explorer has surfaced near the sea. Enjoy a walk along the beach with her as she befriends a host of strange creatures.

Turtle Story by Karthik Shanker and Maya Ramaswamy

Under cover of darkness, baby olive ridley turtles hatch from sun-warmed eggs on remote beaches. One of them, the little hatchling who is the narrator of our story, is delighted to make it across the beach and into the ocean without losing her way or being captured by predators. This charming life story of an olive ridley turtle introduces readers to several interesting creatures along the way.

You can read, download and share ALL these stories thanks to open licensing. You can also translate them to a language you're fluent in and take the stories to more children in more languages.

Tell us, what are you reading this week?

Be the first to comment.

Communities Rising Comes to Pratham Books

Posted by Remya Padmadas on March 06, 2018Zeba Imtiaz is an Assistant Editor at Pratham Books. She writes about Betsy McCoy's recent visit to the Pratham Books office in Bangalore, where she spoke about Community Rising's reading programme and how they encourage reading in children.

We all need inspiration every now and then – especially during busy year ends, when targets are to be met, deadlines to be chased, reflections to be written.

Thankfully, the Pratham Books team got a BIG dose of this inspiration thanks to Betsy McCoy. Betsy is the President of Communities Rising, a not-for-profit established in 2009 that has done some incredible work with children from the villages of Villupuram, Tamil Nadu. Communities Rising aims to spread the joy of reading to all children, through partnerships with school teachers, and by opening after school centres. They directly impact 2000 children, and train teachers to multiply their impact. Along with this, they run specially designed programmes and classes to help students bridge gaps in learning, bring art to children, and encourage social and emotional learning through sharing circles.

Betsy and her team recently visited us at our Bangalore office, armed with baskets of wonderful books and colourful buttons, to share their learnings, and show us what they’ve been up to.

They make the best of often-under-resourced situations with detailed plans and schedules. The Communities Rising team uses a variety of methods and techniques to help early readers gain confidence and find excitement in learning to read. Some of these include -

-

Always providing the children with choices in their reading material, to encourage the growth of independence and personal taste.

-

Regular listening to reading and reading to self and others, to increase confidence and interest in reading.

-

Regularly playing games with the children like letter bingo and scavenger hunts so that the children can have fun while they learn.

They also shared with us their experiences from working with Pratham Books. Bilingual level 1 books are greatly enjoyed by children, as are our colourful illustrations. They mentioned that they would love to explore more level 1 and 2 books as well.

It was a session filled with learnings – especially around the value of choice in books for children and the many little things one can do to instil a reading culture in a classroom. Our team also gained a lot of perspectives on what books are most liked by children and why and it definitely will enrich and impact our process of creating picture books.

Thank you Betsy for the great morning of discussion around children’s books.

Be the first to comment.